Filipinos are eating more rice than the Philippines can produce. That gap is growing. A new study shows the country faced an 18 percent rice shortfall in 2022. That means the Philippines imported 2.3 million more metric tons of rice than it grew. Local production has barely increased since 2017. Meanwhile, rice consumption keeps rising. Researchers from Ateneo de Manila University blame this on stagnant yields, climate shocks, and uneven government support. Their findings were published in the journal PLOS One.

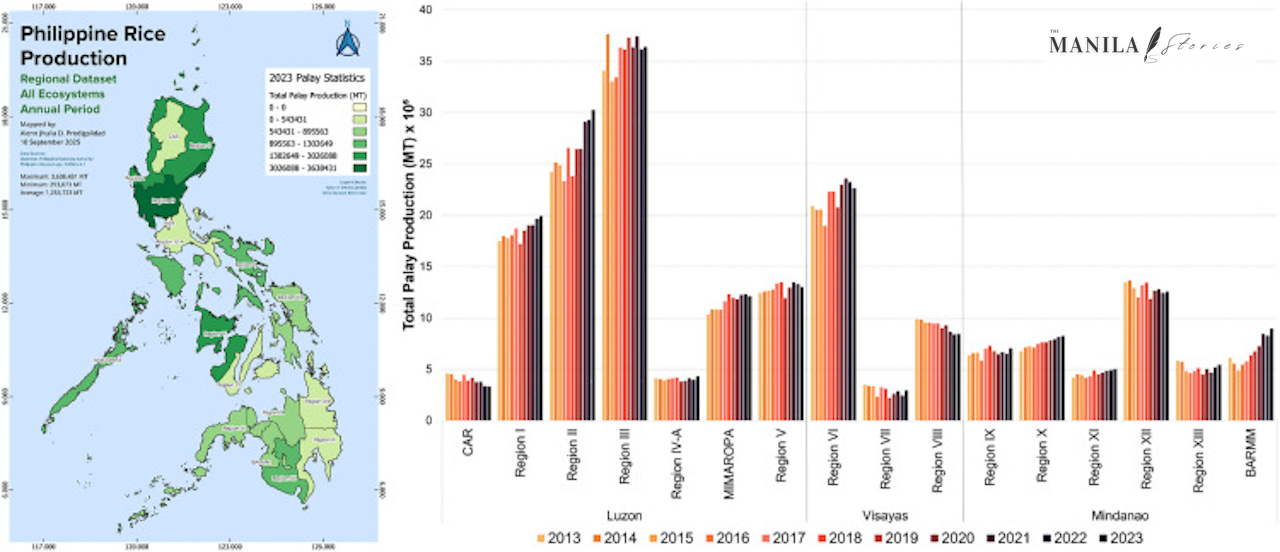

The study comes from the John Gokongwei School of Management and the Department of Environmental Science at Ateneo. It used data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). It looked at rice production from 2013 to 2023. Over that time, palay (unmilled rice) output grew by just 9 percent. It went from 18.4 million to 20.1 million metric tons. The farmland used for rice barely grew. It rose by only 1 percent — from 4.7 to 4.8 million hectares. Yield per hectare improved by only 7 percent. It went from 3.9 to 4.2 metric tons. These small gains can’t keep up with rising demand.

The researchers found regional differences. Some areas are doing well. Others are falling behind. The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) boosted rice output by 40 percent from 2018 to 2023. Cagayan Valley (Region II) grew production by 27 percent. Ilocos (Region I) rose by 16 percent. These regions invested in irrigation. They adopted better seeds. They used farm mechanization. They also had strong local programs to support farmers.

In contrast, Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) and Eastern Visayas (Region VIII) saw declines. CAR’s rice production dropped by 15 percent. Eastern Visayas fell by 11 percent. Farmers lost farmland. Yields stayed flat. Typhoons and droughts hit often. Some farmers switched to other crops. Those crops were more profitable than rice.

Many blame urbanization for losing farmland. But the study found weak evidence for that. City expansion isn’t the main cause. Instead, the problem is slow progress in farming. Poor irrigation limits growth. Climate change brings more extreme weather. Public spending on rice areas is uneven. Some regions get help. Others don’t.

The Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) was supposed to fix this. It was created under the Rice Tariffication Law (RA 11203). It gives funds for seeds, training, and machinery. It was extended to 2031. But the researchers say it’s not enough. National programs don’t reach all regions equally. Lagging areas need more targeted support.

The success of BARMM shows what’s possible. Peace and stability helped. So did investments in irrigation and roads. The region used its RCEF funds wisely. It focused on infrastructure and better farming tools. Cagayan Valley and Ilocos did the same. They prove that growth is possible — even with climate risks.

Experts say the solution isn’t one-size-fits-all. Each region needs its own plan. Irrigation must be strengthened. Farmers need access to modern tools. Support services should be better targeted. Financial help must lower farming costs. Climate-resilient strategies are a must.

The Ateneo researchers are hopeful. They believe local production can still grow. With the right mix of policies and investments, the rice gap can shrink. Reducing import dependence is possible. But it will take focused action. It will take learning from both success and failure.

As the population grows, so does the demand for rice. The Philippines can’t rely on imports forever. Local farming must catch up. The time to act is now.